General Information

Population

Immigration

Emigration

Working-age population

Unemployment rate

GDP

Refugees, Asylum seekers, IDPs

Citizenship

Territory

Migration Authorities

Responsible Body

Line Ministries

Agencies

Key Policy Documents

Law No. 115/1999 on Legal Framework of Immigrants’ Associations

Law No. 67/2003 on Granting Temporary Protection in the Event of a Mass Influx of Displaced Persons

Law No. 41/2003 on Citizenship and Statelessness

Law No. 23/2007 Foreigner’s Act

Law No. 27/2008 on Asylum and Subsidiary Protection

2022-2025 5th National Action Plan for the Prevention and Combat of Trafficking in Human Beings

2025 Cooperation Protocol for Regulated Labour Migration

2024 Action Plan for Migration

Description

Portugal has transitioned from being a country of emigration to increasingly one of immigration. The population of Portugal stood at 10,749,635 in 2024. From 2015 to 2018, the population declined but then rebounded and has continued to grow since 2019. With natural increase remaining negative for the past decade, this growth is driven almost entirely by positive net migration. While the number of emigrants remained relatively stable between 25,000 and 34,000 annually, immigration grew sharply from 83,654 in 2020 to 177,557 in 2024. As a result, the net migration balance more than doubled from 57,768 in 2020 to 143,641 in 2024.

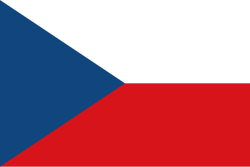

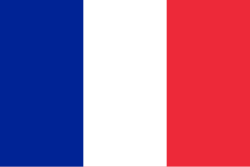

According to UN DESA, 1,127,184 international migrants lived in Portugal in 2024, predominantly originating from Latin America, Europe and Africa. Brazil (173,266) forms the largest group, followed by Mozambique (90,640) and Cabo Verde (76,835), reflecting Portugal’s post-colonial migration links, as well as shared cultural and linguistic ties. Among European origins, France (117,183) is the most prominent, largely due to the return migration of Portuguese-born emigrants and their families, followed by Ukraine (60,056).

Over the past four years, the number of first residence permits issued to non-EU nationals in Portugal increased from 84,397 in 2020 to 121,872 in 2024. Half of all 2024 first permits were issued for employment, followed by family reunification (19.8%), education (13.7%) and other reasons (16.8%). Most first permits were issued to the nationals of Brazil (43,754), India (12,915), Angola (9,716), Nepal (9,411), Cabo Verde (8,355). The same nationality groups were main residence permits recipients since 2020.

Migration plays a significant role in Portugal’s labour market composition. In 2023, 85.7% of the active workforce were Portuguese nationals, while 2.7% came from other EU Member States and 11.6% from third countries, which is slightly higher that the EU average (10.5%). Compared to other EU MSs, Portugal has a slightly lower share of EU mobile workers but a higher share of third-country nationals in its labour market. According to the Portugal Immigration Barometer (2025), most migrants are employed in the construction, agriculture, and services sectors. The labour market participation and sectoral distribution of foreign-born workers in Portugal reflect the country’s strong service economy but also a concentration in certain labour-intensive and lower-wage sectors. Despite the strong participation of migrants in Portugal’s labour market, several sectors continue to face persistent skill shortages, particularly in health care, information technology, engineering, construction, and seasonal tourism. This imbalance reflects both an ageing workforce and limited domestic labour supply, making continued immigration essential to sustaining economic activity and social systems. To better attract skilled migrants and facilitate integration, Portugal allows non-EU students to transition into the labour market under specific residence and permit schemes, easing pathways from education to employment. In 2023, 44,766 international students of bachelor’s and master’s levels studied in Portugal. The largest share of foreign students in tertiary education come from Brazil (30%), followed by Guinea-Bissau (12.2%) and Cabo Verde (11.4%).

When it comes to asylum, Portugal receives a comparatively modest number of applications, placing it among the EU countries with the lowest intake of asylum seekers. Asylum applications totalled 2,675 in 2024, broadly in line with the 2,600 recorded in 2023. These figures reflect a clear upward trajectory since 2020, when applications stood at 900. The top three countries of origin of asylum applicants in 2024 were Senegal (390), Gambia (275) and Colombia (255). Notably, Gambia and Colombia have remained among the leading nationalities applying for asylum in Portugal over the past four years.

Since 2022, Portugal has been hosting people displaced from Ukraine. As of February 2025, 56,700 Ukrainians resided in Portugal under temporary protection. Of them, around 15,800 persons were under 18 years old. Beneficiaries of the EU’s Temporary Protection in Portugal are granted residence, access to healthcare, education, social protection and the labour market. According to the Portuguese Government, specific support mechanisms are in place, including simplified residence permits and integration services.

Portugal continues to experience significant emigration, though at lower levels than in past decades. It remains among Europe’s highest per capita emigrant-sending countries. According to UN DESA, the number of Portuguese living abroad stayed relatively stable over the past 15 years, within the range of 1,727,839 -1,799,179. In 2024, the largest Portuguese communities were in France (585,896), Switzerland (202,178), the UK (193,901) and Brazil (146,697). Portugal recognises its diaspora as a strategic asset, maintaining respective institutional frameworks such as the Secretary of State for the Portuguese Communities to support consular services, cultural ties, political engagement, and diaspora coordination. Remittances have a considerable place in country’s economy, amounting to 4,301 million EUR in 2024 (1.5% of Portugal’s GDP).

When it comes to irregular migration, Portugal is mostly a country of transit, with most irregular entries occurring from African and South American countries via Lisbon airport on the way to other EU states. According to Eurostat, 1,000 non-EU nationals were found illegally present in 2024. Portugal records comparatively low numbers of refusals of entry at its external borders: 1,560 refusals in 2023 and around 1,740 in 2024. Orders to leave remain modest as well, with 750 orders issued in 2024, down from 1,570 in 2023 and 2,190 in 2022. Return rates also remain low, standing at 26.5% return rate in 2024. As a gateway to other EU states and the US, Portugal faces growing misuse of migration channels, with many irregular migrants seeking to regularise their status or obtain forged documents to travel elsewhere.

Portugal is primarily a destination country for trafficking in human beings, with labour exploitation in agriculture as the predominant form, alongside cases of sexual exploitation. According to the Council of Europe’s GRETA 3rd Evaluation Report on Portugal (2022), authorities identified over 1,150 presumed victims between 2016 and 2020. Institutional responsibility is shared between the Commission for Citizenship and Gender Equality (CIG) as national rapporteur. Portugal adopted a 5th National Action Plan against Trafficking in Human Beings (2022–2025)

Portugal’s migration governance framework is shaped by a strong alignment with the EU legislation and a recent institutional overhaul. The cornerstone of it is Law No. 23/2007, regulating the entry, stay, and removal of foreign nationals, complemented by Law No. 27/2008 on asylum and international protection. The framework aims to balance migration control with rights-based integration policies, overseen by the Secretary of State for Integration and Migration and the Secretary of State for Citizenship and Equality. Following the dissolution of the Immigration and Borders Service (SEF) in 2023, administrative responsibilities were transferred to the newly established Agency for Integration, Migration and Asylum (AIMA), while border control and enforcement functions were distributed among the Public Security Police, National Republican Guard and Judiciary Police. The High Commission for Migration together with SEF was also merged to form the new agency AIMA.

On 16 July 2025, Portugal approved major reforms to its Foreigners’ Law 23/2007, marking the most significant tightening of migration rules in recent years. The reform abolishes the manifestação de interesse regularisation pathway, restricts job-seeker visas to highly qualified applicants, introduces a two-year legal-residence requirement for most family-reunification cases, and sets stricter documentation and processing standards for residence permits. A transitional window for those already registered with Social Security and working before 3 June 2024 remains open until 31 December 2025. The reform also creates a dedicated regime for vulnerable minors and obliges the immigration authority to issue residence-permit decisions within nine months, signalling a shift toward a more selective and regulated migration system.

These legislative changes build on Portugal’s Migration Action Plan, adopted in June 2024, which set out 41 measures to restructure the migration system, address administrative backlogs, and strengthen institutional capacity. The Action Plan aimed to clear more than 400,000 pending cases at the newly created migration agency (AIMA), streamline procedures, reinforce cooperation with employers for labour recruitment, and improve integration measures. It also laid the groundwork for phasing out the expression of interest mechanism and moving toward a more skills-based approach to labour migration.

Portugal adopted the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, as well as the Global Compact for Refugees. Moreover, Portugal has also approved the National Plan in 2019 for the Implementation of the Global Compact for Migration. Portugal is a party to several migration dialogues, including the Prague Process.

Relevant Publications