General Information

Population

Immigration

Emigration

Working-age population

Unemployment rate

GDP

Refugees, Asylum seekers, IDPs

Citizenship

Territory

Migration Authorities

Responsible Body

Line Ministries

Agencies

Description

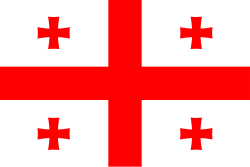

Norway has evolved into a country of immigration, with sustained net inflows and a stable birth surplus driving strong population growth. The population increased from 4,478,497 in 2000 to 5,550,203 in 2024, and is projected to reach 6.15 million by 2050. At the same time, Norway is undergoing a rapid ageing process: within the next decade, the number of older adults is expected to surpass the number of children and teenagers. Between 2015 and 2025, the population aged 45-66 grew by 9.1%, those 67-79 by 32.8%, 80-89 by 27.1%, and those 90+ by 4.8%.

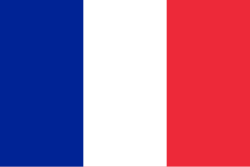

High salaries (average annual earnings above EUR 59,370 in 2024) and consistently strong scores on living-standard and quality-of-life indices make Norway an attractive destination for migrants. Immigration is driven mainly by family reasons, labour mobility, and flight from conflict. According to UN DESA, the stock of immigrants in Norway in 2024 stood at 1,012,404. Whereas national sources place it slightly lower, at 965,113 as of January 2025, constituting 17.3 % of the total population, with the largest immigrant groups coming from Poland (111,376), Ukraine (79,624), Lithuania (43,077), Syria (40,774) and Sweden (37,213). The flow of immigrants rose by 73.5%, reaching 66,077 in 2024 compared with 38,075 in 2020. Of these, 42% came from EU/EEA countries, especially Poland, Romania and Sweden, while 15% arrived from Asia, mainly Syria, India and Pakistan. Immigrants work across a wide range of sectors, but mostly in healthcare and social work, construction, services and sales.

In 2024, Norway issued 23,589 first-time residence permits to non-EU nationals, a 23 % decrease from 30,670 in 2022, reflecting a tighter immigration policy. Most permits were issued for family reunification (29%), employment (11%), and education (10%). The largest recipient groups were nationals of Syria (2,598), followed by India (1,785) and Vietnam (1,620). The stock of valid permits equally decreased from 183,000 in 2022 to 134,832 in 2024. Most of the valid residence permit holders came from Syria (17,220), followed by the UK (11,720) and India (8,460).

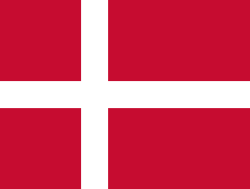

The number of international students in Norway had been rising for several years, supported by a wide offer of English-taught Bachelor’s and Master’s programmes. This trend reversed in 2023-2024 following the introduction of tuition fees for non-EU/EFTA students, which led to a decline in enrolments. In response, Norway expanded scholarship opportunities for students from developing countries. By 2025, numbers began to recover, with 24,250 international students, up from 23,650 in 2024. Most international students come from Europe, particularly Germany, Sweden, and France. In contrast, Norwegian students studying abroad primarily choose the UK, United States, and Denmark.

Emigration from Norway reached 31,968 in 2024, including 9,159 Norwegian citizens, down from 34,011 in 2023. The largest non-Norwegian groups leaving the country were Ukrainians, Poles, and Swedes, with Ukraine, Poland, Sweden and Denmark being the main destinations. Departures reflect both foreign nationals returning to their countries of origin and Norwegians moving abroad for work or personal opportunities. In 2024, the stock of Norwegians abroad numbered 120,891, with the largest communities in Sweden (39,914) and Denmark (20,886) and Poland (13,653).

In 2025, Norway hosted 333,514 persons of concern, including 117,043 asylum seekers, 51,706 resettlement refugees, and 72,048 individuals admitted through family connections. Most originated from Ukraine, Syria, and Eritrea. Norway received 4,970 asylum applications in 2024, slightly below the 5,375 recorded in 2023. The annual resettlement quota remained at 1,000.

In terms of international protection, Norway hosted 333,514 persons of concern in 2025, including 117,043 asylum seekers, 51,706 resettlement refugees, and 72,048 individuals admitted through family connections. Most originated from Ukraine, Syria, and Eritrea. Norway received 4,970 asylum applications in 2024, slightly below the 5,375 recorded in 2023. The annual resettlement quota remained at 1,000 in 2024.

Since February 2022, Ukrainians became the largest group seeking protection in Norway. The government introduced temporary collective protection in March 2022, and from October that year, beneficiaries were no longer counted as asylum applicants. Applications for collective protection reached 34,732 in 2022, 35,166 in 2023, and 18,321 in 2024, while Ukrainian asylum applications remained low (810 in 2024; 906 in the first nine months of 2025). Legislative amendments facilitated rapid entry, labour-market participation and access to education, and adjustments were also made to the Child Welfare Act to accommodate increased arrivals. Effective from 1 January 2025, Norway extended the maximum duration of temporary collective protection from three to five years, aiming to reduce administrative pressure and allow more time to assess conditions in Ukraine. Later in 2025, the scheme was tightened, excluding dual nationals with another safe country and applicants from regions deemed safe; additional travel restrictions were also introduced, with re‑entry permits revocable if beneficiaries return to Ukraine without valid reason.

Between 2021 and 2024, the number of people found illegally present in Norway rose steadily, reaching 3,515 in 2024, up from 3,360 in 2023, 2,305 in 2022, and 1,430 in 2021 – an increase of about 146% over four years. In 2024, the largest groups were nationals of India, Pakistan, and Ukraine. By contrast, refusals of entry declined to 310 in 2024 from 405 in 2022. The number of third-country nationals ordered to leave fell to 3,640, roughly half the 2021 level. The top nationalities ordered to leave were Pakistan, Türkiye, and Colombia. Returns following an order to leave remained stable, with 1,085 returns in 2024, mainly involving nationals of Russia, Türkiye, and Colombia.

Norway is primarily a destination – and to a lesser extent a transit – country for human trafficking. Authorities identified 97 victims in 2024, a 19% decrease from 2023, and assisted 183 victims, down from 216. Most victims originated from Central and South America, especially Colombia and Venezuela, and were predominantly women exploited in sex trafficking. In 2024, police opened only 19 trafficking investigations, the lowest number since 2007, though convictions increased and all identified victims received assistance. The government also expanded funding for specialised shelters, introduced new oversight rules for temporary work agencies, and strengthened the Transparency Act to better prevent forced labour in supply chains.

Norway’s immigration laws are based on the Immigration Act of 2008. The Directorate of Immigration is the central agency in the Norwegian immigration administration implementing the government’s immigration and refugee policy. In the integration field, Norway’s Integration Act remains the cornerstone, regulating Norwegian language and social studies training, the introduction programme, and municipal responsibilities. The integration efforts are vital given that the employment rate among migrants is on average 10% lower than that of the non-immigrant population in Norway.

In 2025, Norway pursued a more restrictive course in migration policy, reflecting growing domestic concern over capacity and sustainability. Key changes include the implementation of the Return Strategy 2025-2030, which aims to streamline both voluntary and forced returns. Emphasising humane processes, the strategy also strengthens reintegration support and bilateral co‑operation with origin countries. Stricter subsistence requirements for family immigration were introduced in January 2025, raising the income threshold for sponsors. Recognition of qualifications has been restructured. Foreign education is now more rapidly assessed, with a five‑day fast-track option for employers. A new automatic recognition scheme supports smoother access to the labour market, especially for citizens from Ukraine and EEA states.

In cooperation with ICMPD, Norway opened migrant resource centres (MRC) in Iraq that help build capacity for local and national government and provides comprehensive information on migration-related challenges and opportunities, raising awareness of migration processes, protecting migrant’s rights, and preventing irregular migration.

Although not an EU member, Norway is a member of the European Return and Reintegration Network, which aims to strengthen, facilitate and streamline the return process in the EU through common initiatives. The aim is also to promote durable and efficient reintegration to countries outside the EU. As of 2024 Norway signed re-admission agreements on return with 31 countries.

Norway voted in favour of the Pact on Migration and Asylum and support its implementation. Norway is an EMN observer state. It is also a member state of the Prague and Budapest Processes.

Relevant Publications